October 28: Embroidered samplers then, graffiti throwups now

For our October 2025 meeting, professor/researcher/type designer Craig Eliason illuminates the forces shaping lettering beyond pen and type

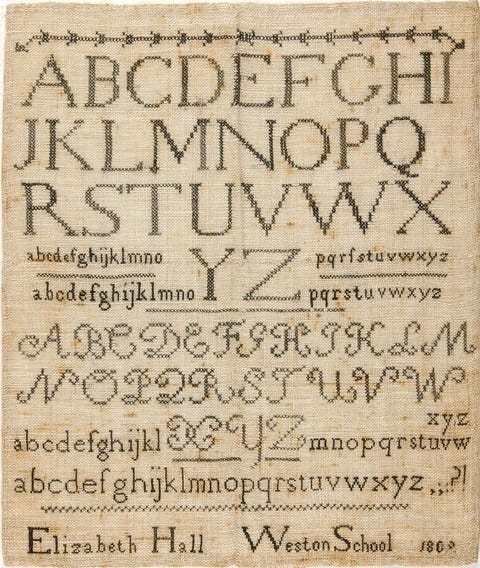

Typeset texts and the manuscripts they emulated have largely shaped our sense of what letters should look like. But some texts are neither typeset nor written. This talk investigates two such lettering practices: nineteenth-century embroidered samplers and contemporary graffiti writing. It will show how differing purposes and mediums shaped letters in these traditions, and will uncover how emergent letterform norms were instituted.

Meeting Details

Tuesday, October 28 2025

6:00 PM: Arrival and Mingle

6:30 PM – 8:00 PM: Presentation

Mpls Central Library - RKMC Room (Second Floor) 300 Nicollet Mall, Minneapolis

This event is free, and open to anyone who loves type.

By the nineteenth century, a predominant form of embroidery was the “sampler,” which recorded the stitches learned by the embroiderer, typically a young girl. Most of these included alphabets, verse, and/or testimonies of faith, in letters cross-stitched on the grid formed by the fabric’s weave, demonstrating the talents, literacy, and piety of their makers. Among them we find consistent lettering styles, striking precursors of today’s pixel fonts. Norms for these letters were reinforced by teachers and by earlier samplers themselves.

In the world of contemporary street art, graffiti writers run letters of a moniker together in “tags,” sometimes done as “one-liners” with uninterrupted flow from the spray can, or more elaborate “throwups”or “throwies.” Here letterforms are not only influenced by the aerosol tools; they must also be both personal and quick. Norms are again learned from existing examples and more experienced creators. Artists will keep sketches of throwups they plan, complete, or admire in “black books.” These sketchbooks, visual records of their personal engagements with lettering craft, are a fascinating analog to the samplers of centuries before.

Nineteenth-century embroidered pieces served as a record of obedience and conformity to expected gender roles; present-day illicit throwies are on the contrary gestures of defiance and self-expression. But both are useful case studies for how letterform norms adjust to circumstances, mediums, and means of reinforcement.

For more about Craig’s work, check out his foundry website, Teeline Fonts.

Super excited for this presentation — hope to see you there!

This sounds like a fascinating event. I wish I were closer!

I have to disagree about “Nineteenth-century embroidered pieces served as a record of obedience and conformity to expected gender roles”. This was work done in schools. Embroidery work on samplers was a demonstration of literacy and of the high value placed on the accomplishments of girls. Conformity and obedience is always expected in schools, even today. But these girls found creative forms of expression even within the strictures of schools. Look at the beauty of that sampler you showed (from a Quaker school, Westtown, using the classic Roman style.) I think they serve as a record of a fantastic legacy of the work of girls, signed and dated with pride, tens of thousands of them.